This isn’t a polished research article. It’s not about data, models, or papers. It’s about being in the middle of a rapidly evolving crisis, where the flooding of the Praid salt mine in Romania led to surface collapses and salty water getting further into rivers, and what it felt like to use science in real-time, while standing on shifting terrain both literally and professionally. I wanted to share some personal reflections from our time at Praid.

Various images from Praid salt mine, with friends, family and students (2014-2023)

Romania has numerous salt mines, and many of them have parts open to tourists. These sites are not only a cultural attraction, but also a valuable scientific window into an otherwise hidden underground world.

As geologists, and especially since Dan holds a PhD in salt tectonics and has an active scientific interest in salt, we have visited many salt mines in Romania, as well as in other locations.

But of all…Praid was my favorite salt mine…

Dan and I have been to Praid countless times. We’ve been there by ourselves, with friends, family, students, and researchers over the years, licking the walls and trying to understand its complex geology.

When we found out it was all flooded (the active, the touristic, and the historical mine), and the roof of the historical mine could collapse, with (at that point) no clear idea of the potential impact and timing. We discussed with Salrom, and they asked if we could help in any way.

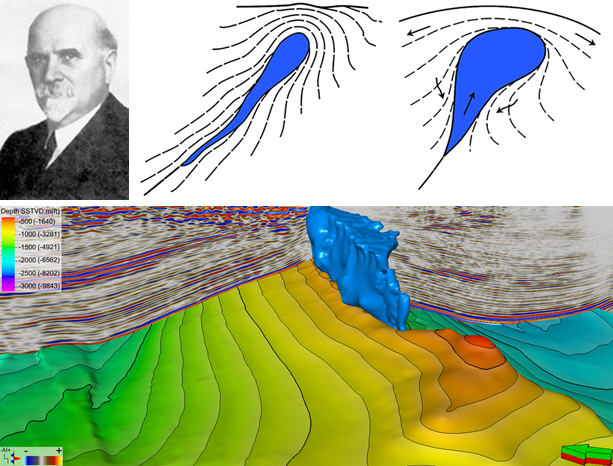

We arrived to find a high-pressure situation unfolding fast. Our background in geology and even our prior publications on salt tectonics became secondary to the urgent needs of the field. This wasn’t a research paper, it was real-time crisis management, where mining engineering, hydrology, risk assessment, construction, and more had to be coordinated on the fly.

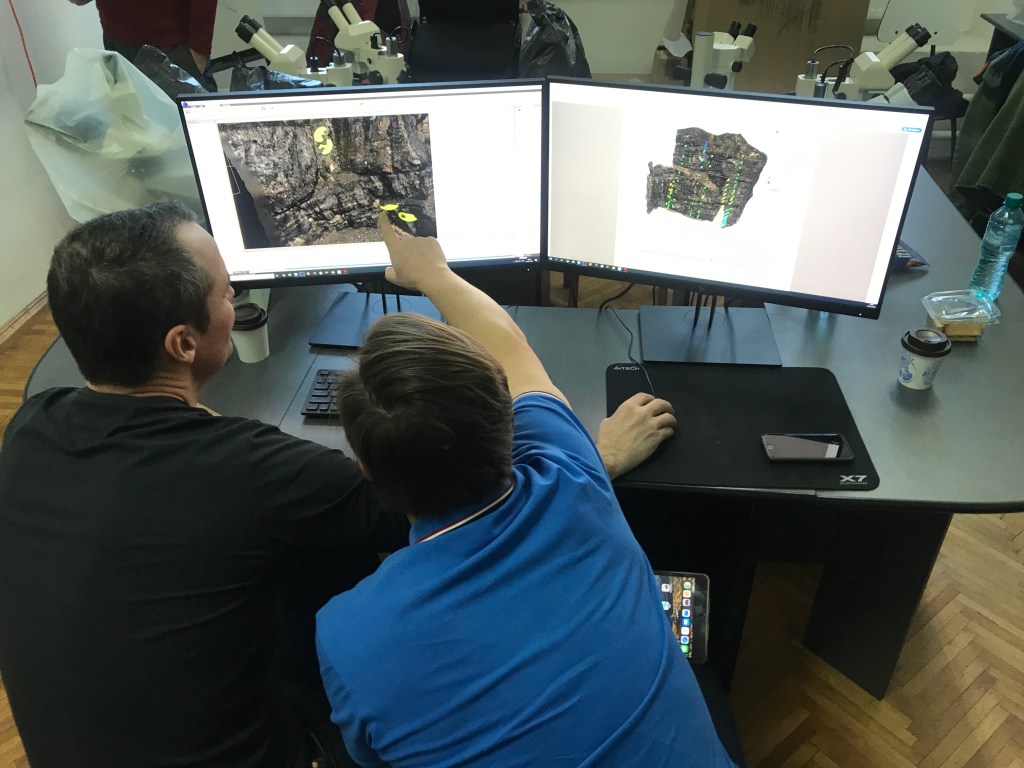

Still, our skill set proved useful. With experience in drone mapping, GIS, computer modeling, and structural interpretation, we quickly stepped into our role and were happy to fit into this significant effort.

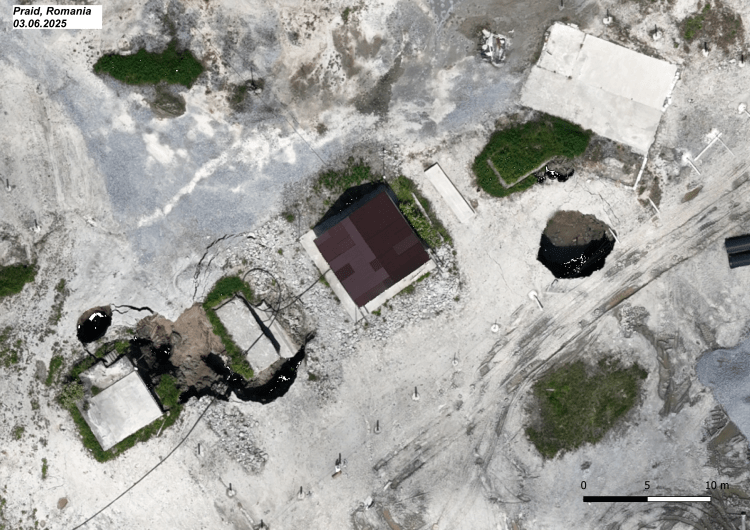

We were monitoring sinkholes – surface depressions or collapses that form when underground cavities (like those in the salt mine) become unstable. They can appear suddenly and dangerously, especially when triggered by water infiltration. At Praid, we were watching the landscape deform daily, an unsettling, high-stakes demonstration of geology in motion.

We began documenting the situation day by day, flying drones at 5:00 am, building 3D models, and creating daily maps of the rapidly changing terrain. These visual updates became essential tools for on-site teams to plan the next steps.

It turns out that monitoring a deformation area that develops from one day to the next is equally fascinating as interpreting structures that formed millions of years ago, albeit very frightening. It was like watching millions of years develop on fast forward. The landscape looked different each day.

Each day, a different landscape…a new map, a new road… a new plan…

We thought we’d be there for just a couple of days, but ended up staying for two long weeks that felt like months, rapidly acquiring, processing, and interpreting enough data to fill a PhD project. We are also grateful to our colleagues from the GeoEduLab of INCDFP, with whom we conducted a large-scale mapping of the entire area on June 3, the first day of mapping.

On our final day, down to our last clean T-shirt (which, to be fair, mine was Dan’s), just minutes before leaving, we had one more meeting, sitting with ministers, state secretaries, generals, hydrologists, engineers, and construction leads. The crisis didn’t stop just because we had to leave.

We left, as our university duties were piling up, but not before transferring part of our drone-mapping knowledge and interpreting workflows to the local Salrom staff, so they can continue this monitoring in the long term. We are grateful for the support they offered in those couple of weeks, and we continue to be available whenever they need help or have any questions.

What unfolded at Praid is difficult to fully grasp without being on site. The contrast between the tireless, hands-on efforts in the field and the distant certainty of outside commentary was striking. Simplified or misleading opinions emerged, often missing the real depth and difficulty of the situation.

I am thinking about all the people actively working there. I hope they stay safe in the field. I hope their efforts are not in vain, given the rapidly changing landscape. I hope it won’t rain so they can catch a break…